PAPER: nderstanding women's uptake and adherence in Option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in Papua, Indonesia: A qualitative study.

Understanding women’s uptake and adherence in Option B+ for prevention

of mother-to-child HIV transmission in Papua, Indonesia: A qualitative study

Reference

Lumbantoruan, C., Kermode,

M., Giyai, A., Ang, A., & Kelaher, M. (2018). Understanding women's uptake

and adherence in Option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission

in Papua, Indonesia: A qualitative study. PloS one, 13(6),

e0198329.

Christina Lumbantoruan1,2*,

Michelle Kermode2,

Aloisius Giyai3,

Agnes Ang3,

Margaret Kelaher1

1 Centre for Health

Policy, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2 Nossal

Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria,

Australia, 3 Provincial Health Office, Papua Provincial Health Office,

Jayapura, Papua, Indonesia

MY CONCLUSION:

Methodology

|

Result 1

|

Result 2

|

Result 3

|

Summary

|

In-depth Interview

20 women living with HIV (10 women who were non-adherent,

10 women who were 100% adherence)

20 PMTCT workers at two main referral hospitals for PMTCT

in Papua

Pregnant and postpartum

HIV-positive women with live birth who attended the ANC at Jayapura Hospital

and Abepura Hospital, as well as health workers who provided PMTCT services

at both health facilities.

|

Supportive factors of PMTCT uptake and adherence:

*Good quality post-test HIV counselling

*Belief in the efficacy of ARV

*a partner who did not prevent women from seeking PMTCT

care; sero discordant and HIV positive partners were more reported to be more

supportive than partners who refused to get tested

*good relationship with health workers

*No. discrimination in health setting:No. excessive use of

precautions, including masks, and gloves

|

Key barriers for PMTCT participation:

*doubts of ARV efficacy, particularly for asymptomatic

women

*unsupportive partners

*Women’s concerns about community stgma and discrimination

*long-waiting list in hospital

|

Strategies to enhance women’s engagement to pmtct services: counselling

women with doubts regarding arv efficacy early program: enhancment of support

for women in need; a continuous campaigns; availability of adequate human

resources; reduction of long waiting times, and increased privacy during

return visits

|

Concern of long-term

adherence for long-term of accessing PMTCT service

Option B+ as current national

policy for pregnant women in Papua has improved detection and enrolment of

HIV-positive women, health facilities need to address various existing and

potential issues to ensure long-term adherence of women beyond the current

PMTCT program, including during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding.

|

Abstract

Background

Despite a more proactive

approach to reducing new HIV infections in infants through lifelong treatment

(Option B+ policy) for infected pregnant women, prevention of mother-to-child

transmission of HIV (PMTCT) has not been fully effective in Papua, Indonesia.

Mother-to- child transmission (MTCT) is the second greatest risk factor for HIV

infection in the commu- nity, and an elimination target of <1% MTCT has not

yet been achieved. The purpose of this study was to improve understanding of

the implementation of Option B+ for PMTCT in Papua through investigation of

facilitators and barriers to women’s uptake and adherence to antiretroviral

therapy (ART) in the program. This information is vital for improving program

outcomes and success of program scale up in similar settings in Papua.

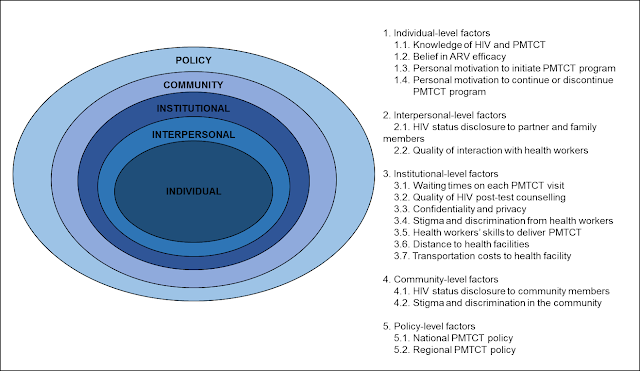

Methods

In-depth interviews were

conducted with 20 women and 20 PMTCT health workers at

two main referral hospitals for PMTCT in Papua. Development of interview guides

was informed by the socio-ecological framework.

Qualitative data were managed with NVivo11 software and themes were analysed

using template analysis. Factors influencing women’s uptake and adherence in

Option B+ for PMTCT were identified through final analysis of key themes.

Results

Factors that motivated

PMTCT uptake and adherence were good quality post-test HIV counselling, belief

in the efficacy of antiretroviral (ARV) attained through personal or peer

experiences, and a partner who did not prevent women from seeking PMTCT care.

Key barriers for PMTCT participation included doubts about ARV efficacy,

particularly for asymptomatic women, unsupportive partners who actively

prevented women from seeking treatment, and women’s concerns about community

stigma and discrimination.

Conclusions

Results suggest that PMTCT

program success is determined by facilitators and barriers from across the

spectrum of the socio-ecological model. While roll out of Option B+ as current

national policy for pregnant women in Papua has improved detection and

enrolment of HIV-positive women, health facilities need to address various

existing and potential issues to ensure long-term adherence of women beyond the

current PMTCT program, including during pregnancy, childbirth and

breastfeeding.

IMPORTANT QUOTATION

In 2012, the World Health Organization

(WHO) recommended Option B+ as a novel approach to eliminate mother-to-child

transmission (MTCT) of HIV [1]

This approach requires

routine HIV testing for all pregnant women and lifelong antiretroviral therapy

(ART) for positive cases irrespective of HIV clinical status or CD4 count [2].

Based on WHO criteria,

elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) of HIV is achieved when

there is less than 2% MTCT in non-breastfeeding populations or less than 5% in

breastfeeding popula- tions, and if per 100,000 live births there are no more

than 50 new pediatric infections [3].

1.

World Health Organisation. Programmatic

update: Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing

HIV infection in infants. 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/

programmatic_update2012/en/

2.

World Health Organization. Consolidated

guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV

infection: Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health

Orga- nization. 2013.

3.

World Health Organisation. Global

guidance on criteria and processes for validation: Elimination of

mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis. 2nd edition. WHO. 2014.

Available from: http://apps.

who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259517/9789241513272-eng.pdf;jsessionid=

0EB32F7E22EC7CA9EF12029AE8170794?sequence=1

Prior to Option B+, PMTCT

performance in Indonesia was suboptimal with 86 new HIV infections in 1,145

(7.5%) live births among HIV-positive women who received the interven- tion [9]. During this period, PMTCT implementation was

limited because of stigma and dis- crimination, long distances to health

facilities, and long waiting times [10–12].

4.

Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia.

Rencana aksi nasional pencegahan penularan HIV dari ibu ke anak (PPIA)

Indonesia 2013–2017. 2013. Available from: http://www.kebijakanaidsindonesia.

net/jdownloads/Publikasi%20Publication/rencana_aksi_nasional_pencegahan_penularan_hiv_dari_

ibu_ke_anak_ppia_-_2013_2017.pdf

5.

Hardon AP, Oosterhoff P, Imelda JD, Anh

NT, Hidayana I. Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Vietnam and

Indonesia: Diverging care dynamics. Social Science & Medicine. 2009; 69(6):

838– 845.

6. Oktavia M, Alban A, Zwanikken PAC. A qualitative study on HIV

positive women experience in PMTCT program in Indonesia. Retrovirology. 2012;

9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/

articles/PMC3360250/pdf/1742-4690-9-S1-P119.pdf

7.

Trisnawati LM,

Thabrany H. The role of health system to support PMTCT program implementation

in Jayawijaya regency. Indonesian Health Policy and Administration. 2015; 1(1):

8. Available from: http://

journal.fkm.ui.ac.id/ihpa/article/view/1729/575

Data Analysis

The research team followed

eight steps for conducting template analysis:

Step 1. Development of a

priori themes based on literature related to the PMTCT program in Indonesia

and other low and middle income countries, as shown in Fig

1.

Step 2. Data familiarisation

by reading interview transcripts.

Step 3. Preliminary data

coding by highlighting parts of transcripts relevant to a priori themes

and new information relevant to research questions.

Step 4. Refinement of a

priori themes to integrate new emerging themes.

Step 5. Organisation of

themes into groups and establishment of hierarchical and lateral rela-

tionships between groups.

Step 6. Development of an

initial coding template after coding five interviews that contained the

greatest variation in responses.

Step 7. Application of the

initial coding template, and revision after coding of another five interviews.

Step 8. Finalisation of

the coding template and its application on the full data set.

RECRUITMENT: IN

HOSPITAL SETTING

Women

who agreed to participate were asked about their time and location preference

for interviews. All women preferred to be interviewed on the same day at the

hospital while waiting for their appointment, other than one woman who

requested to return for an interview the following day. Length of interviews

ranged from 15 to 45 minutes with an average of 29 minutes, excluding

icebreaking conversation that took around 5 minutes per interview.

Health

worker participants were individually approached by CL and were informed about

the voluntary nature of the study. All health workers (20/20) participated

voluntarily in inter- views. As preferred by health workers, interviews were

conducted at the hospitals after working hours or during less busy hours.

Duration of interviews with health workers was between 16 and 60 minutes with

an average of 38 minutes.

Result

Participant characteristic

Data from 40 interviews,

20 HIV-positive women (10 women who were non-adherent, 10 women who were 100%

adherent) and 20 health workers (health workers providing PMTCT service at both

hospitals for at least one year), were analysed.

Stigma and

discrimination at health facility: Discrimination was not observed

during field observations at both health facilities. There was no excessive

use of precautions, including masks and gloves, in executing routine tasks or

when meeting HIV+ women. Women partici- pants also claimed they were not

treated differently (20/20) after HIV diagnosis. No participant reported

discontinuing treatment due to discrimination at the health facilities. [pp 10]

Interpersonal-level

factors. HIV status disclosure and partner support: The majority of women

in this study (16/20) had disclosed their HIV status to their partners

and requested they get tested for HIV. Sero discordant and HIV positive

partners were reported to be more supportive than partners who refused to get

tested. The latter could be mentally or physically abusive, and prevented

women from adhering to treatment. The presence of domestic violence (3/10)

before and/or after HIV status disclosure became a main reason for PMTCT

non-adherence reported by women. [9]

Institutional-level

factors. Health workers explained the increasing number of patients they

managed at CST clinics because HIV+ pregnant women no longer stopped ART after

childbirth/breastfeeding as occurred pre- Option B+. They explained major infrastructure

and human resources changes were less likely to occur in the short-term, so

the PMTCT program was adjusted to meet available resources. Consequently, there

was a reduction in quality of care, such as long wait

times and lack of privacy, but women and health workers rarely identified

these as barriers to PMTCT uptake and adherence. Frequently mentioned

facilitators of program adherence were respect for

confidentiality and stigma-free care from health workers. [9]

Factors motivating uptake

and continuation in the program were a constellation of individual,

interpersonal, institutional, and policy factors. Factors associated with

increased uptake and adherence included good quality post-test HIV counselling,

belief in the efficacy of ARVs to prevent transmission

and improve health, confidentiality of HIV status, absence of stigma and

discrimination at health facilities, positive women-health worker

relationships, and free HIV services [25–32].

PERSONAL BELIEF OF

EFFICACY IN ARV, EVEN WITHOUT ACTIVE ENCOURAGEMENT FROM THEIR PARTNERS

PARTNER’S SUPPORT,

PARTICULALRY FINANSIAL SUPPORT IS STILL IMPORTANT

The women in our study

did not necessarily require a partner who actively supported their

treatment in order to remain in the program, unlike findings in other studies [23, 25, 37, 38]. A majority

of women continued their treatment due to personal

belief in ARV efficacy even without active encouragement from their partner.

However, consistent with findings of other studies, partner

support is important to retain women who are financially dependent on the

partner [25, 26,

37, 39, 40].

GOOD RELATIONSHIP WITH

HEALTH WORKERS

Women-health worker

relationships: The relationship between health workers and women seemed to

be satisfactory as all women (20/20) described health workers as either friendly

or kind, while health workers felt ‘kasihan’, or sympathy, for women and

their children. A minority of women (2/20) mentioned health workers becoming

angry with them when they missed their doses, but they believed it was ‘a sign

of caring’, rather than dislike. One woman, however, preferred health workers

explaining things without being angry. [11]

SEEKING HEALTH SERVICES

OUTSIDE THEIR NEIGHBOURHOOD: AVOID OF COMMUNITY STIGMA

Stigma and

discrimination in the community: Perceived stigma and consequent discrimination

in the community was seen by women as an important barrier to continued

participation in the PMTCT program. Hence, a large proportion of women (16/20)

sought treatment at a health facility outside of their neighborhood to avoid

detection of HIV diagnosis by family members or friends. For this group, this

meant travelling between 45 and 60 minutes using public transportation (n = 7)

or continuing PMTCT treat- ment at referral hospitals instead of returning to

nearby satellite PHCs (n = 9). Of 10 women who were adherent to PMTCT

treatment, only one woman lived less than 30 minutes from the health facility.

[11

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE WOMEN’S ENGAGEMENT TO PMTCT SERVICES: COUNSELLING

WOMEN WITH DOUBTS REGARDING ARV EFFICACY EARLY PROGRAM: ENHANCMENT OF SUPPORT

FOR WOMEN IN NEED; A CONTINUOUS CAMPAIGNS; AVAILABILITY OF ADEQUATE HUMAN

RESOURCES; REDUCTION OF LONG WAITING TIMES, AND INCREASED PRIVACY DURING RETURN

VISITS

Conclusions

Our study argues the clear

importance of motivating factors that outweigh barriers to PMTCT uptake and

adherence at five levels of the socio-ecological framework. The roll out of

Option B + as policy for pregnant women in Papua, which means inclusion of HIV

testing as a routine part of pregnancy screening, has improved identification

of HIV-positive women and their enrolment in the program. Further strengthening

of the PMTCT program is necessary to ensure continuous enrolment of new cases

while maintaining adherence of women in HIV care by addressing barriers or

potential inhibitors to long-term treatment. These

include availability of strategies to identify and counsel women with doubts

regarding ARV efficacy early in the program, establishment of support for women

in need, a continuous campaign to reduce stigma and discrimination at the

community level, availability of adequate human resources, reduction of long

waiting times, and increased privacy during return visits.

Comments

Post a Comment